Our Story

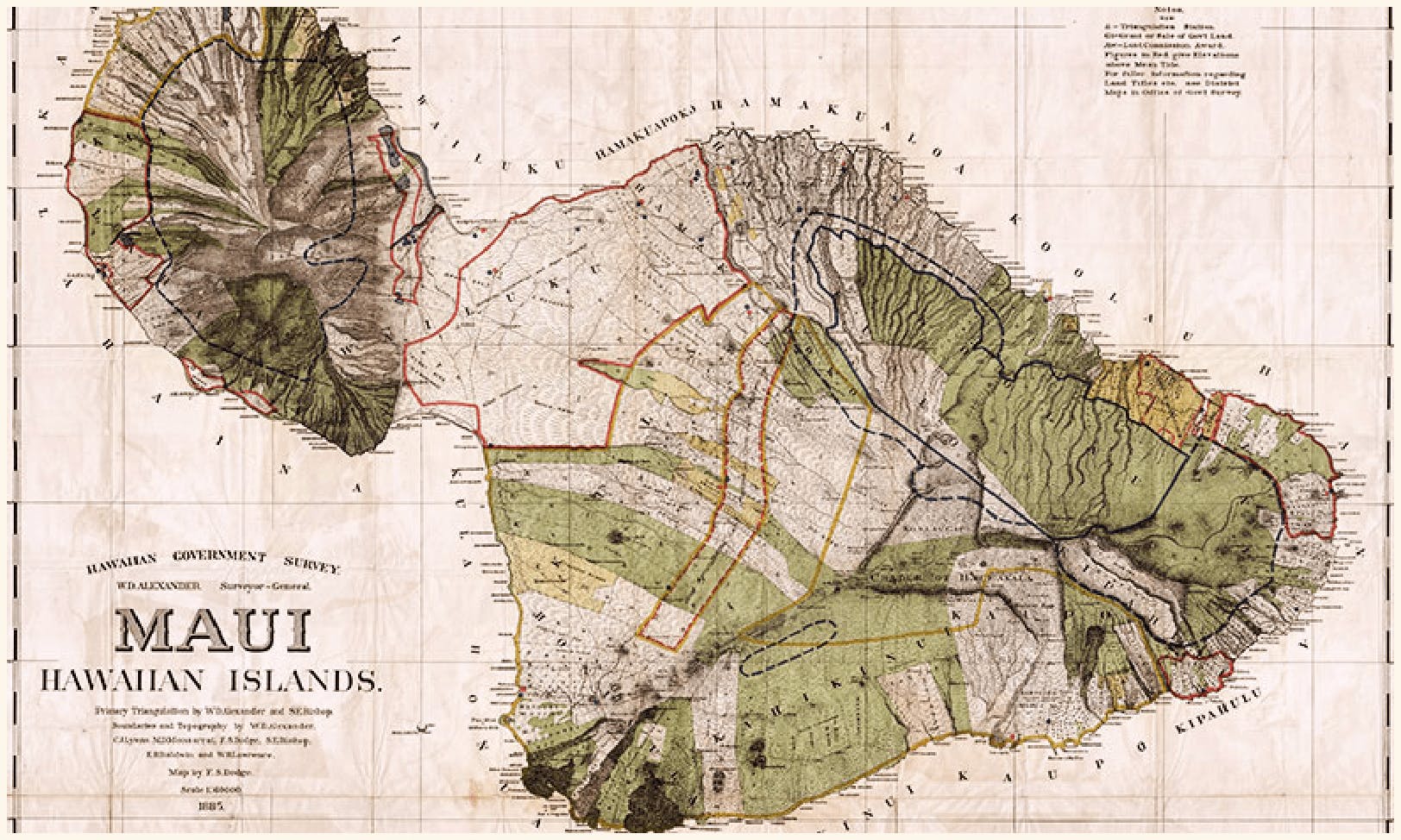

Long before visitors flocked from around the world to Mama’s Fish House, a very young Floyd and Doris Christenson flew to Hawaii on the new TWA prop-jet that had cut flying time to the islands to 13 hours. Hawaii had just become a state and a friend had urged them to visit Maui.

There were no resorts on Maui, only the Pioneer Inn in sleepy Lahaina ($10/night). To reach the deserted beaches of Kaanapali and Wailea, they had to walk through thick groves of thorny Kiawe trees. A Tahitian family urged them to visit Tahiti and the South Pacific which they said was still an undiscovered paradise.

The search for a boat

They returned to California determined to live on an island in the Pacific. They started looking for a boat to sail to the South Pacific. They wanted to explore old Polynesia, the island kingdoms that spanned the Pacific from Easter Island to New Zealand to Hawaii.

In Newport Beach harbor they found a 38 ft. two-masted ketch named “Marinero” (Spanish for “sailor”). It was the perfect boat for long ocean voyages but it was not for sale. They contacted the wealthy owner and asked if he knew where they might find a similar boat, telling him of their plans. He said that he had always wanted to sail to the South Pacific but his age and health now made that impossible. He was in the middle of a divorce and fearful that his wife would take the boat from him. When he learned of their plan to sail to the South Pacific, he agreed to sell Marinero to the Christensons for an amount that they could afford, saying, “I will never do it. You do it for me.”

Learning to Navigate

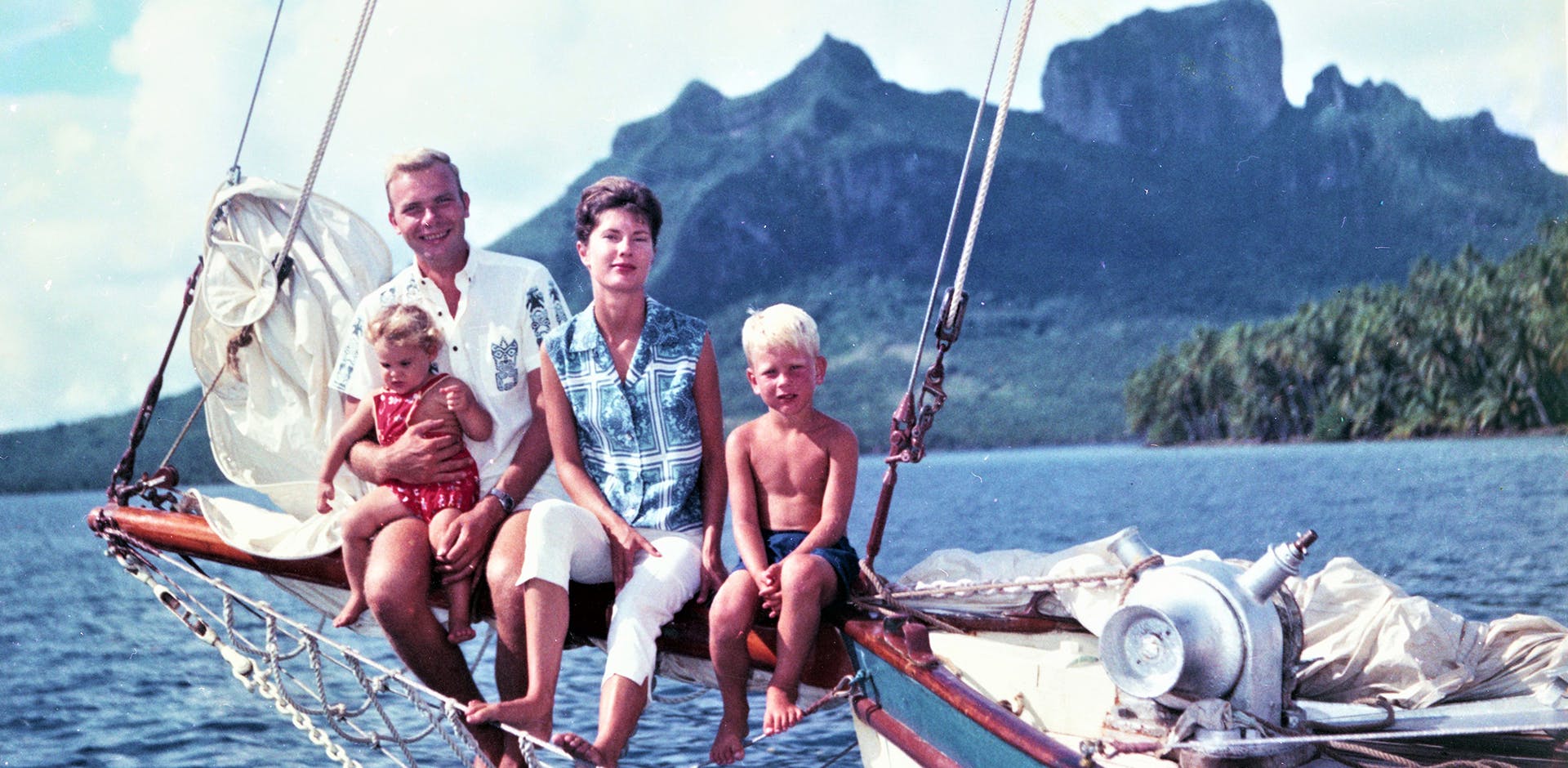

They lived aboard for over a year, practicing navigation and sailing to the islands off Southern California. Finally, Floyd and Doris and their 2½ year old boy Keith waved goodbye to their crying parents and sailed out of San Diego harbor, steering Marinero towards the Marquesan Islands, 3,600 miles south.

It was 1960. No electronic navigation aids existed then and Floyd navigated by sun sights taken with a sextant, just as sea captains had done for hundreds of years. Using a marine clock that was calibrated with time signals broadcast by shortwave radio, Doris called out the exact second that was noon. Floyd measured the angle of the sun from the horizon with his sextant. Using formulas from a book, Marinero’s position could be determined to within two miles.

Sometimes their self-steering device worked and sometimes it didn’t. When it didn’t, they took turns at the wheel, four hours on and four hours off. Occasionally they rigged the boat to stay in place (heave to) so they could catch up on their sleep.

Little Keith was fascinated by the schools of porpoises that would play in the boat’s wake, surfing the waves and leaping out of the water. Occasionally a whale as big as Marinero would swim so close it could almost be touched.

There were occasional storms and many squalls that deluged the boat with very welcome fresh rainwater. Sometimes the wind would completely die for days. They would take turns going for swims, or hang over the bowsprit and watch the many tiny critters skittering across the surface of the water.

Unless the weather was bad, Doris always cooked the family a hot meal. Her tiny galley contained a 2-burner gimbaled stove that stayed flat no matter what angle the boat was taking. She rigged a folding oven over the stove to cook bread, cookies and sometimes bake pies. The sink had two hand-pumps: one with fresh water for cooking, one with salt water for cleaning up. No refrigeration, but squash, pumpkins and cabbage lasted through most of the trip, as did eggs dipped in wax. Lemons and limes buried in sand stayed edible for a couple of weeks and in good weather, Daiquiris with fresh lime were served at sunset.

“Sunset was generally the big event of the day, a 360 degree panorama of every-changing colors,” Floyd would later write. “The nights were magical. If there was a moon, it lit the white sails and reflected off the waves in thousands of sparkly lights. If there was no moon, the sky would be filled with stars and the ocean would be black and invisible. We steered towards the Southern Cross which rose higher and higher every night. When the sun started to rise, the entire world – sky and water – would turn increasingly bright shades of red, then orange and finally there would be sunlight and the blue Pacific.”

Nuka Hiva

As Marinero approached the equator and the windless doldrums, it became unbearably hot and steamy. The winds and the seas were chaotic. At night the entire boat would be lit by explosions of phosphorescent light from deep in the ocean. Vague outlines of huge animals could be seen in the deep.

On Thanksgiving Day, Floyd was able to connect with Washington DC radio operators for the first time. Astonished by Marinero’s location, they patched them into the US telephone system. Doris called her parents and wished them a Happy Thanksgiving from the equator.

Once through the doldrums and then the fickle light winds of the Horse Latitudes, they reached the steady winds of the Southern trades. It was good sailing and Marinero moved at a steady 5 to 6 knots.

Floyd was growing increasingly anxious. Would the island of Nuka Hiva be where it was supposed to be? Then the waves began to change, land-birds were seen and a puffy white cloud tinted green underneath was spotted on the horizon. It was their island, Nuka Hiva.

On a glorious morning, 36 days out of San Diego, Marinero sailed into the deep harbor of Tai O’Hai bay. The island was stunningly beautiful, the bay bordered by sheer green cliffs with waterfalls cascading down them. They anchored and rowed ashore. It took a few days to relearn how to walk on solid ground.

After a few weeks a young Marquesan came aboard as crew. Isaac was just 20 and an excellent fisherman. For three months they explored the islands of the Marquesas, sometimes sailing to villages that had never been visited by a sailboat. In the more remote villages, they would be met by canoes paddled by kids bearing gifts of fruit and fish. Dozens of them would clamber aboard and sleep overnight on Marinero’s deck.

Floyd had an 8mm movie projector on-board and would show cowboy movies to the awed villagers who had never before seen a motion picture. Floyd also carried a Polaroid picture camera, taking pictures to give people who had never seen themselves in a picture.

In one village, the village chiefs declared a “fete”, a party for the entire village, to celebrate the Christenson’s visit. The morning of the fete, while the food was being prepared, Floyd and some of the men rode horses with wooden saddles up narrow mountain trails to sacred places with what they called “living tikis”. Once there, they explained their religion and what they believed.

The ladies of the village spent the morning preparing the feast. Doris was confined to sitting on a coconut mat where she was fed bananas and treated like royalty.

By early afternoon the entire village arrived, all of them dressed in colorful pareu’s (lava-lavas), flower leis and flower hei’s (head dresses). Long woven mats were spread on the grass. An impressive array of food was served in hand-carved wooden bowls and plates. There was no beer or wine because the monthly supply boat was late, but a good supply of home-made sour orange beer was on hand.

As evening approached young Marquesians performed traditional erotic dances to the music of guitars, ukuleles and multiple drummers. The rhythm of the drums and the fast Tahitian guitar strum was infectious. Soon everyone was dancing. The Fete lasted late into the night, the coconut trees lit by flaming torches and the music and drumming echoing off the mountains.

They visited many islands, sometimes anchoring in a quiet lagoon beside an abandoned village. They would gather mangoes and papayas from the trees, watercress from freshwater streams and find the best breadfruit (there are many varieties of breadfruit).

Isaac would catch fish, lobster, octopus and sometimes turtle. He could rest motionless at depths of 30 feet, waiting for the right fish to come to him. Sometimes he was able to snatch sweet mantis shrimp from their holes in the lagoon floor.

On dark moonless nights they would catch fresh water prawns using flashlights to illuminate their eyes, spearing them with sharpened nails tied to the end of sticks.

At sunset the family would sometimes build a small campfire on the beach and cook their dinner. Doris would always have a fresh salad. A whole breadfruit would be baked in the fire and then eaten with canned butter. Dessert was fresh or canned fruit (Isaac loved canned peaches).

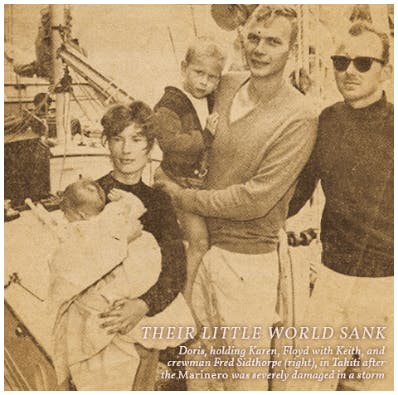

After three months in the Marquesas, Doris declared that it was time to sail to Tahiti where there were good French doctors and medical facilities. Many months later, Karen would be born.

Tahiti

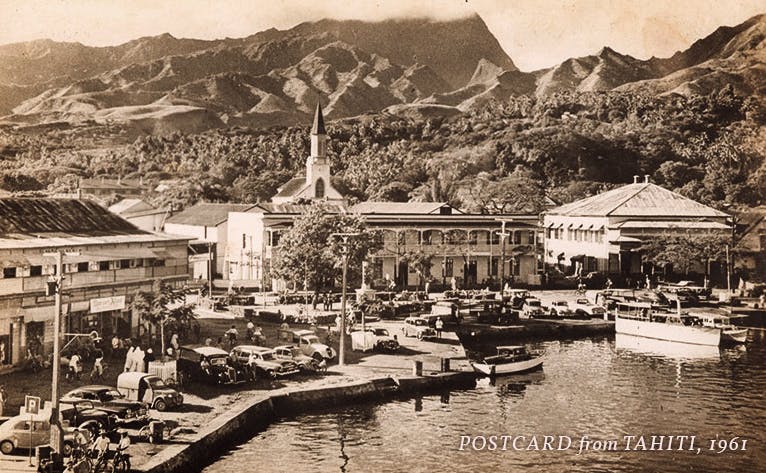

The family lived in Tahiti and the neighboring islands for over a year. They would sail to the bays and lagoons of Moorea, Raiatea and Bora-bora, but mostly they remained tied to the quay that fronts Papeete. 25 or 30 yachts from all over the world were always tied up beside them and everyone lived on their boats.

The lagoon was protected by a reef that surrounded Tahiti like a necklace. Sailing canoes would fly across the blue waters of the lagoon and swimmers dove in the coral reefs for fish. Children swam off the boats or jumped off the quay, chasing fish between the coral heads that rose up from the bottom of the lagoon like big trees. In the distance, beyond the outer reef, the jagged peaks of Moorea Island rose above the horizon.

The street bordering the quay was generally full of Tahitians riding their bicycles, Vespas and motorbikes. Across the street was Café Vaima, owned by an American and a favorite of the yachting families. Dining was open air, under big spreading trees or inside with big open windows.

Vaima served traditional Tahitian dishes and French bistro fare, accompanied by French wine or Papeete’s Hinano beer. Lunch might be a salad of fish marinated in coconut milk and lime juice and served in a coconut. (Tahitian fish salad and Hinano beer are served at Mama’s Fish House). Floyd and Doris dreamed of someday opening their own Vaima.

Papeete was filled with young girls from the outer islands who came to party with boyfriends in the local bars and dance halls. The cafes and dance halls were famous throughout the South Pacific. The biggest, Quinn’s, was filled every night with locals and seaman from the cargo and passenger ships that stopped in Papeete and it stayed well past midnight. The Tahitian bands were excellent. “Quinn’s Girls” performed traditional dances on a stage high above the crowd.

Doris, who was 23, became friends with many of the girls in Papeete and as she grew bigger, the girls began calling her “Mama Doris”. Three days after Karen was born, they both returned to Marinero. Baby Karen slept on a floor cushion in the aft cabin, between Floyd and Doris’ bunk.

They remained in Papeete for a few months while Karen grew stronger. Inside the lagoon the water was flat calm and the yachts sat in the water almost motionless. The tide in Tahiti is never more than one foot and a wide wood plank connected the sterns of the yachts to the shore. Doris would “walk the plank” carrying baby Karen on her hip, with Keith in tow.

tonga and new Zealand

Isaac had long since returned to his Marquesan village. A young American sailor from another sailboat joined Marinero. There were now three adults, four year old Keith and baby Karen aboard the 38 ft. sailboat. Every locker was filled with provisions, baby food, toys and cotton diapers. (At sea, diapers were cleaned by sticking them into a manila rope and towing them behind the sailing ship. They were then rinsed out in fresh water and dried on the rigging.)

Their first stop was Rarotonga Island, 750 miles Southwest. The Cook Islands were then owned by New Zealand and the food there was a mix of British and Polynesian. Avarua, Rarotonga was a comfortably small island town and the harbor was good. It was a relief that everyone spoke English. Floyd & Doris made many friends and hoped to return to spend more time there.

After a month they sailed on to the Kingdom of Tonga, then down to New Zealand.

Marinero was hauled out onto dry dock in Auckland. Six months were spent installing a new engine (which had quit for good in the Marquesas) and completely refitting the boat. The refit was harder and took longer than expected and cold winter arrived. It was too late in the season to sail back to Tahiti so they headed north to tropical New Caledonia to wait for spring. There was good French cooking there and good French canned goods (the NZ food and canned goods were barely edible).

A few hundred miles out they were hit by a hurricane with wind gusts of 120 MPH. Some large ships were damaged and some smaller boats went missing. Using continuous power and a small try-sail, Floyd was able to keep Marinero pointed into the wind. The seas were mountainous and the boat was swept underwater a few times, but the continuously running motor kept her bilges dry. The eye of the hurricane passed right over the top of them.

Marinero was blown 400 miles off course and finally emerged from the storm eight days later in the “horse latitudes” between the equator and the Southern tradewinds, too far off course to sail to New Caledonia. The winds in these latitudes blew in the opposite direction of the tradewinds and Floyd decided to use these contrary winds to sail all the way back to Rarotonga.

Winds were light and progress was slow. On the way, little Karen took her first steps and learned to walk across the cockpit. They had not provisioned for such a long trip and it was a month before they reached Rarotonga. They had plenty of water and baby food but by the last week they were down to pancakes and the occasional flying fish that flew onto the boat. Doris’ galley stove was out of gas and she had to cook on a single burner alcohol stove which she cradled between her legs.

In Rarotonga Floyd worked for four months as the Captain/navigator of a 95 ft. cargo ship. The ship had a crew of 19 and carried copra, oranges, cattle, turtles and 20 seasick passengers between Rarotonga and the remote Cook Islands. Then the Christensons sailed back to Papeete and tied up at their old spot on the quay across from Café Vaima.

Restaurant Beginnings

They stayed in French Polynesia for the next six months. Letters from friends in Lahaina told of plans to develop Maui as a major tourist destination. New hotels were being built beside the beaches of Kaanapali, now accessible from new highways. The Christensons decided that if they were ever to open their dream restaurant, it would be on Maui.

The Christensons decided that if they were ever to open their dream restaurant, it would be on Maui.

Doris flew to Maui with the children and Floyd assembled a crew of experienced seaman for the sail up to Hawaii. The trip to Hilo took just 19 days. The crew left and Doris and the children came aboard for the final voyage to Maui. Floyd and Doris sailed into Lahaina harbor with tears in their eyes. After four years living aboard Marinero, they had at last reached their island and their home.

Settling Down in Paia

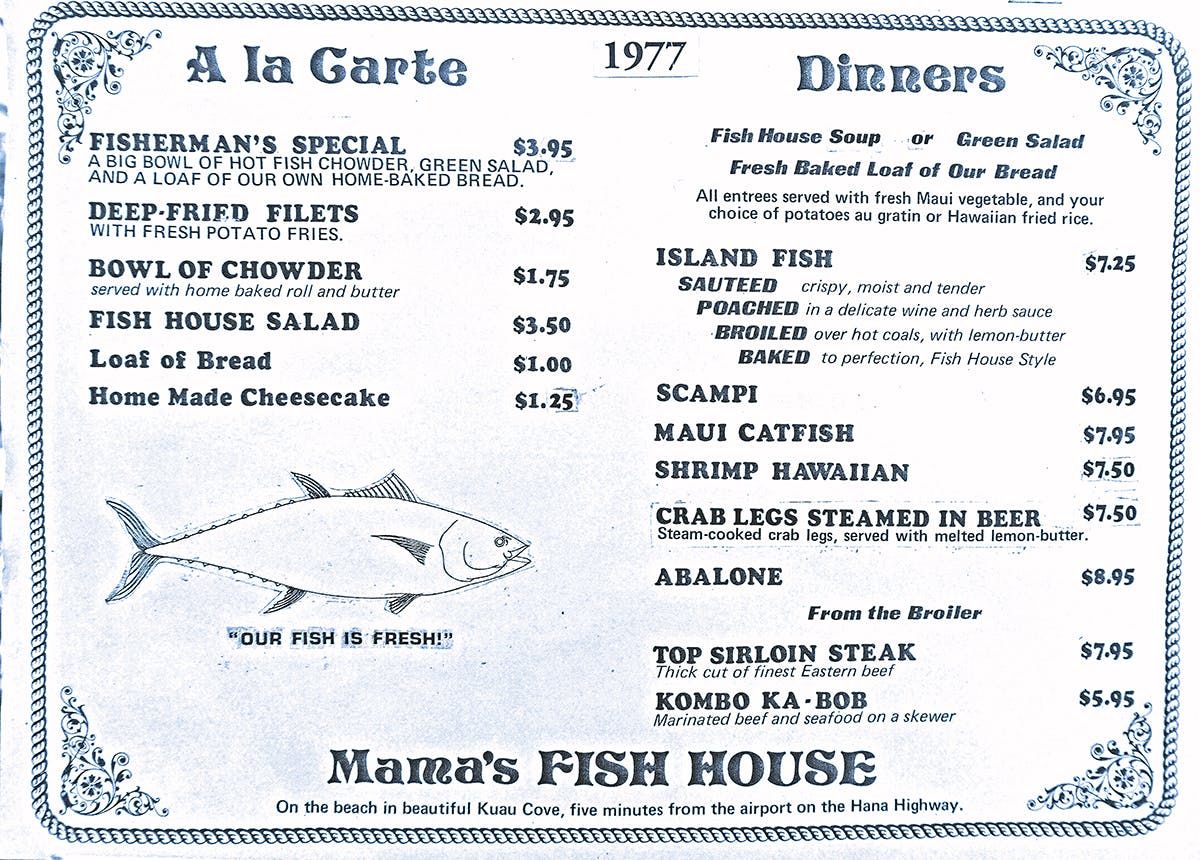

Nine years later they bought the property that is now Mama’s Fish House. The first cook, a close friend, persuaded Doris that the right name for the restaurant was “Mama’s Fish House”. Maui restaurants were mostly steak houses and they wanted to everyone to know that Mama’s served fresh Maui fish.

The restaurant soon had a small group of loyal local customers, but few tourists ever stopped on the north shore. Those that did were leery of local fish. They wanted frozen Mahi-mahi from Japan, and they wanted it cooked until it was bone-dry.

Fresh Fish

New hotels were opening and young people were moving to Maui to work in them. Many became loyal Mama’s customers once they learned how good fresh fish can be when properly prepared. Mama’s Fish House became a popular neighborhood restaurant, known for good fresh fish. Customers chose what fish they wanted and then chose any one of six ways to cook it.

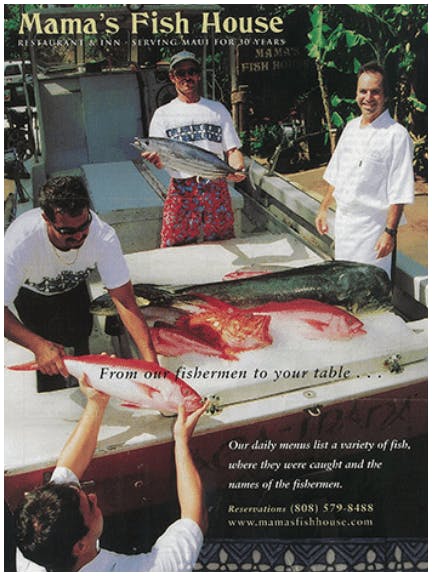

In the beginning there were few full-time fishermen, but as Mama’s grew, so did the fishing community. They brought their fish directly to the restaurant where it was filleted and served within 24 hours. Floyd printed the names of the fisherman and where the fish was caught on the daily menu.

Artists, Craftsmen and chefs

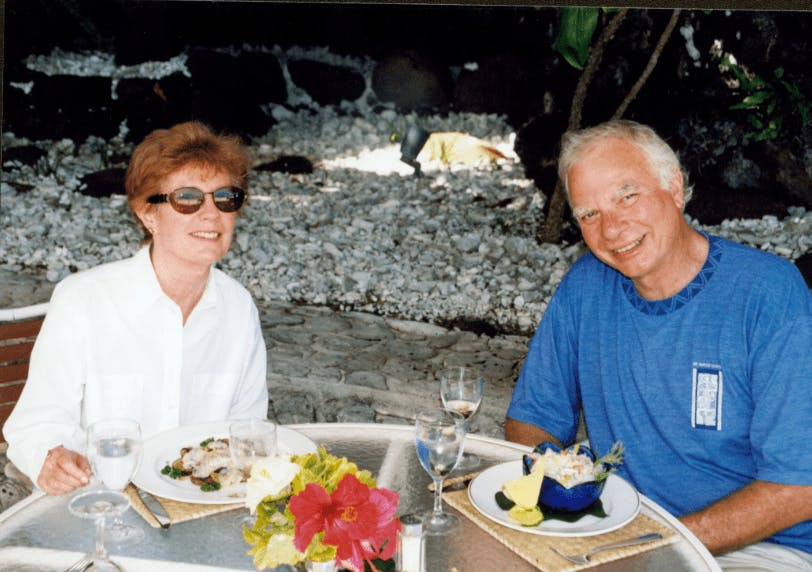

In 2000, Maui-born Perry Bateman became Mama’s first Executive Chef. He had started at Mama’s at age 19 and his cooking skills impressed Doris. Floyd and Doris decided to move beyond being just a good neighborhood restaurant.

They were determined to showcase the fish and the foods of Polynesia to their customers. They re-introduced breadfruit and other long-neglected Polynesian foods to their menu and they encouraged local farmers to grow the best organic produce.

From the beginning they were joined by artists, craftsman and chefs who shared their dream of creating a memory of old Polynesia. Many of them – and now even their children – still work at Mama’s and they love to tell Mama’s story to visitors.